AGI Through Turing Machines

Created: August 16, 2015 / Updated: December 21, 2025 / Status: in progress / Readability: technical / 6 min read (~1107 words)

It is conjectured that the human mind can be completely reproduced by a computer and an appropriate program. What this means is that by using simple I/O to interact with the world as well as control structures (if/then and loops), we should be able to reproduce (but not necessarily replicate, that is copy the exact activity that occurs within the brain) what goes on in our mind.

Turing machines represent the foundation of how computers (automata) work. It is thus highly relevant to learn how Turing machines are described and how they work so that we may be able to understand potential limitations to this approach (if there are any) or any algorithm-based approaches.

- "However, merely updating the list/sequence of instructions of the program is not a display of intelligence." yet "First, moving itself is to some degree intelligence."

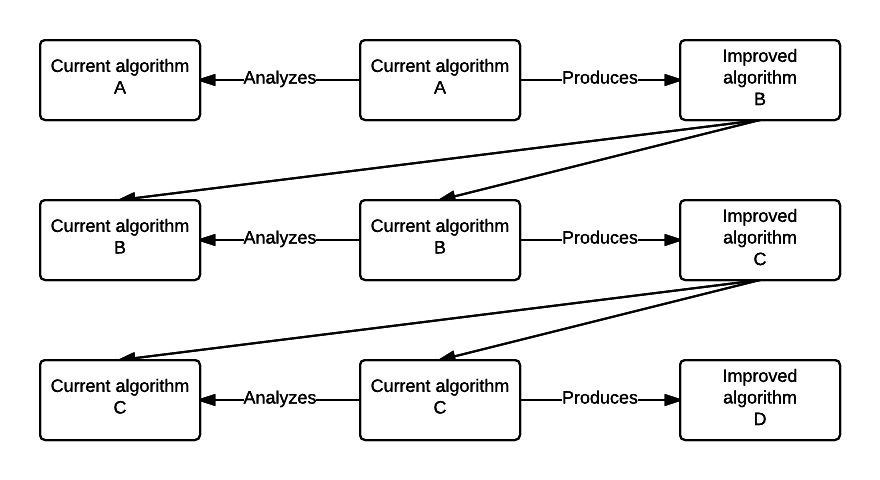

The simplest form of initial AGI software would have to be one that rewrites itself.

At the lowest level, computers are governed by a set of instructions, such as ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV, AND, OR, MOV, JMP and other similar instructions.

If we go a level lower, we can refer to Turing machines, for which the elementary operations are moving left, moving right, reading from the current square on the tape (memory) and writing to the current square. Another important part of a Turing machine is its state, which relates to its instruction table/program, that is to say "if you are in state X, and you see Y on the tape, do Z and put yourself into state A".

[A tape for data input/output, a head to read the data, a state register to store working information and and instruction table/program (describes how input data produces output data).]

For an AGI to rewrite itself, its program would have to update itself during execution. However, merely updating the list/sequence of instructions of the program is not a display of intelligence.

The difficulty at this level of abstraction is that nothing will appear intelligent. Moving left/right while reading and writing symbols on a square cannot be qualified as intelligent.

Turing described a couple of instructions that are what I would consider low level intelligence. (reference?)

First, moving itself is to some degree intelligence. Without movement, change cannot occur (although writing is also a change). Left/Right movement is equivalent to moving from state A to state B (or to state C) in a state machine.

Second, reading and writing is the second form of low level intelligence. Reading allows the agent to learn from the world while writing allows it to communicate with the world.

Third, it can change its internal state. According to the original description of a universal computing machine by Turing, such a machine may be placed in any of its m-configurations, which are part of its standard description or number description, which is finite.

In itself, this basic machine can do three things:

- I/O (read/write) with a target (the tape)

- Change target (move the tape left/right, changing the cell we are interacting with)

- Update its internal state (within a finite state space)

Turing machines can be "simplified" (or more appropriately, restricted) into state machines. As stated by the definition of a Turing machine, a program is given, which indicates to the machine what it should do if it sees a particular symbol while reading the tape. This is equivalent to stating the state machine states and transitions conditions.

Now, when a Turing machine moves its reading head (or moves the tape), there is no real state machine equivalent. The purpose of the moving head is to read a new sequential transition condition. In other words, the action of moving left or right isn't very important, what is more important is what will end up being read, which will influence the transition the state machine will take. In doing so, it may write to the block it just read, but again, that is not important in the context of the state machine.

Similarly to Turing machines, it is easy to see that a state machine may enter a loop and possibly never come out of it (the halting problem). Given the state machine diagram, one may be able to assess that certain starting point and transitions will result in the state machine reaching a terminal state (the program terminates), for instance in any state machine diagram that is acyclic (does not contain any cycle).

In a Turing machine, we are given an instruction table, or program. Such instruction table contains a list of 5-tuples definition the current state, the scanned symbol, the symbol to print, how to move the tape and the next state of the machine.

In the case of the state machine, we have a current state, the scanned input and the next state of the machine. Certain state machine called transducers will generate an output based on the given input and/or state. In a sense, we can liken this "ability" of the machine to the ability of Turing machines to move the tape and to write to it. In other words, we can say that the state machine should move some tape left/right based on the input/state as well as to write on that tape some information. Again, moving a tape within the context of a state machine is irrelevant in the sense that was we are interested in is the stream of input token and its impact on the state of the state machine and the output actions.

The important difference between a Turing machine and a state machine is how it uses the tape to store additional information. In a state machine we do not really have any storage of information. In automata theory, there is an intermediate automaton called the pushdown automaton between state machines and Turing machines which can push an unlimited amount of state onto a stack but only use the symbol on the top of the stack determine which transition to execute. Turing machines are equivalent to pushdown automatons that have been made more flexible by relaxing the last-in-first-out requirement of its stack.1

The list of instruction then become a set of steps the machine will walk through. Those steps